Minerals for Aging Soils

By Dr. Lee Klinger, Ph.D.

Now that I’ve passed the half-century mark I feel fortunate to be only slightly worse for the wear as my body copes with getting older. None-the-less, lingering aches in my joints and bones are telling signs that my body is aging. These aches come as no surprise of course.

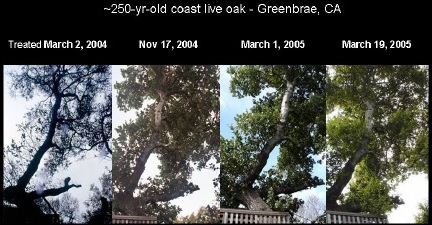

Scientific studies indicate that as organisms grow old their metabolisms slow down and their tissues acidify. Acidification leads to a departure from the chemically balanced, neutral pH state preferred by most living systems, around pH 7. I’m quite aware that the buildup of acidity in the human body is associated with any number of health problems, from osteoporosis to diabetes. All the more reason to stay active, eat good organic food (grown here on the farm), and take mineral supplements to buffer my body against the buildup of acids that would attack my bones and cartilage. But that’s only half of the story. For as I am aging, so are the plants and the soils around me. It makes sense that if I’m to going to keep getting the proper set of nutrients needed to balance my pH, then I have to be sure the plants and soils that sustain me are getting the same set of nutrients. So twice a year I give the fields and trees where I live a hefty dose of mineral fertilizer (the same mineral supplements I take each morning at breakfast) which enriches the soil and reduces acidity. The results of these treatments on the trees have been rather astounding. As the photos below indicate, oak trees that are diseased and dying can be shown to quickly recover in response to the mineral amendments. In this case I have applied minerals topically to both the bark and the soils. To understand better how it is possible to get such positive results, let me delve further into the concepts of aging and acidification.

Why do living systems tend to acidify with age? Ultimately, it comes down to the fact that life is comprised largely of water, a universal solvent. At the molecular level, living cells and tissues behave more like solutions of chemicals in water than anything solid. Acidification is the inevitable result of one key property of water, its differential solubility of acidic and basic materials. Basic substances, which add to the alkalinity of a system, are more soluble in water than substances that acidify. Thus, over time as water flows through an aging system, alkaline substances are dissolved away more quickly and tend to become depleted relative to acidic substances. Because of this fact, microbes, animals, plants, ecosystems, and soils are all confronted in life with the same problem as they age they tend to acidify.

Aging effects in forests and soils have long fascinated me. In college, I spent a couple of summers working for tuition money as a choker setter in the timber fields of southeast Alaska. Flying to and from the logging camps I was amazed, shocked in fact, to see vast regions of pristine old-growth forest that were covered in dead and dying trees. Most folks there said the forest was merely succumbing to “old age”. While I couldn’t really disagree, I remember at the time feeling there was something lacking in the explanation.

Time lapse of a treated oak tree

Eventually, I turned this fascination into a scientific career, one which has provided me the opportunity to conduct detailed studies on the succession (development) of plants and soils in southeast Alaska and in dozens of other ecosystems around the world. My results have consistently been in agreement with those of other scientists studying succession, namely that the soils of aging ecosystems, especially the surface soils, tend to become more acidic over time. Along with this comes a depletion of basic minerals (e.g., those rich in calcium, sodium, potassium, magnesium and numerous trace elements) and an overabundance of acidic minerals (e.g., those rich in silica, aluminum, and iron) in the surface soils. Nature, of course, has evolved various ways to help ecosystems buffer against soil acidification. The most common ways are disturbance events such as wildfires, floods, and volcanoes which provide an influx of minerals that rebalance the nutrients and ameliorate the acidity of surface soils.

In agricultural ecosystems, burning has long been known to be a reliable means of maintain healthy rangeland and cropland. When more acidic conditions develop, cropland soils are typically treated with amendments of agricultural lime, a practice that goes back at least 3000 years. Tilling also helps to ameliorate acidity and balance the pH of the soil by bringing to the surface any alkaline minerals that have been leached downward.

On-the-other-hand, many commonly-used fertilizers and pesticides are acidic in nature, so that whatever their intended effect, they have an additional effect of raising the hydrogen ion concentration (ie. lowering the pH) of the system. The cumulative impact of such practices on soil chemistry can be astonishingly large. University of Wisconsin scientists report that 30 years of “normal” agricultural acidic inputs caused their test field soils to age the equivalent of 5000 years of acidic inputs from natural sources.

While most of us don’t pay much attention to small patches of mosses and lichens growing on our trees and soils, it turns out that these darling little critters are acid factories. Mosses and lichens break down bark tissue and are known to be both indicators of, and contributors to, acidic soil conditions. Ever notice that diseases and pests seem to arise in places where mosses and lichens flourish?

Another important source of acidity is in the rain (and snow). Even in unpolluted regions rainwater is mildly acidic, usually reported to be around pH 5.7, and is rather depleted in minerals. While efforts to moderate acid rain continue to help reduce the impact of acidification in soils, rainwater will never be free of all acidity.

One of the main outcomes of acidification that is often overlooked is its effect on trace minerals. Typical analyses of plant tissue reveal the presence of all 88 naturally-occurring elements, though most are found in only trace amounts. Some scientists are beginning to suspect that many, perhaps even all of these so-called trace elements play some important, though as yet unknown, role in the biology of plants (and animals). Trace elements, to varying degrees, are susceptible to leaching by acids and, thus, can become depleted in surface soils. This means that, in the long run, remineralizing soils with lime alone may not be what works best. At some point the soils will also require amendments with a balanced set of trace elements.

Where I live, along the Central Coast of California, the problem of acidification is severe. The moss and lichen cover is heavy and soils are depleted in alkaline minerals and numerous trace elements. Assisted by various diseases and insect pests these conditions have led to the demise locally of thousands of oaks and other old-growth trees.

The forests here originate from the time of the native people, who we know used fire in a systematic fashion to manage oak woodlands for acorn production. Shifting management practices brought on by white settlement of the region in the late 1800s, along with the strict fire protection measures of recent decades, has allowed soils to age and acidify, resulting in elevated rates of mineral loss due to leaching. Alkaline minerals, especially calcium, are major components of bark, the tree’s first line of defense against pests and diseases. In healthy oaks, the calcium content of the bark tissue is high, twice that of nitrogen. The trees around here, however, are not healthy, and deep splits and cracks have developed in the bark of the oaks as well as the sycamores, the walnuts, and many of the fruit trees. These openings serve as ready points of entry for canker diseases, fungal pathogens, bark beetles, etc.

Understanding trees and soils in this way has led me to develop effective methods for solving the acidification problem. Needless-to-say, these methods involve direct measures of intervention to help buffer the pH and remineralize soils. Most common mineral fertilizers such as aglime, potash, and rock dust I have found are variously effective in ameliorating acidity and replacing depleted nutrients. In the ten or so years of mixing and applying soil minerals there are two products that stand out as favorites. The first is Azomite(R) Soil Remineralizer (both micronized and granular), a natural volcanic mineral product that is loaded in trace elements, over 70 total elements in a typical analysis. Mined and processed in Utah, Azomite(R) has been around for more than 60 years. The product comes with numerous testimonials and scientific studies to back the claims of promoting growth and suppressing disease in plants and animals. It is used agriculturally both as a mineral fertilizer for cropland soils and as an additive in fish and livestock feed. Azomite(R) is also being added to many compost teas to enhance their efficacy.

The second product is Azomite(R) Soil Sweetener, a granulated mixture of micronized Azomite(R) and a micronized calcium carbonate limestone also produced in Utah. The Azomite(R) Soil Sweetener is proving to be very effective in helping trees and crops on the more acidified soils. The added calcium appears to be helping trees and vines recover more quickly from a state of decline. As an all-purpose aglime, one that contains a balanced set of alkaline-rich minerals and trace elements, I would put Azomite(R) Soil Sweetener at the top of the list. (See www. azomite.com for more information on both of these products.)

Whether or not you have acidification problems in your soils, it is prudent to consider following a fertilizing regimen that pays attention to keeping proper levels of alkaline minerals and trace elements in the soil. Sooner or later aging will present itself as a problem in every soil type, and knowing what to do about it will help extend the health of the soil and all that it sustains.

Dr. Lee Klinger is an independent scientist and consultant living in Big Sur, CA. Contact info: PO Box 664, Big Sur, CA 93920

Reprinted with permission from Lee Klinger and Ranch & Farm News.

Support us on Patreon

Thank you for joining us today! Please become a member of RTE and support us on Patreon. Unlike many larger organizations, we work with a team of determined and passionate volunteers to get our message out. We aim to continue to increase the awareness of remineralization to initiate projects across the globe that remineralize soils, grow nutrient dense food, regenerate our forests’ and stabilize the climate – with your help! If you can, please support us on a monthly basis from just $2, rest assured that you are making a big impact every single month in support of our mission. Thank you!

John Carraway

October 12, 2011 (8:16 pm)

I’d like to recommend adding sea water to your tree therapies. Take two potted plants to which you add your usual fertilizers, except with one you use sea water and the other you use fresh water. I think there is something biological in sea water that will increase productivity. Of course, both pots must have plenty of topsoil and mulch to encourage micro-organisms. As for your own aging concerns, always take plenty of MSM and antioxidants to ward off any problems.

Janet Dahle

April 25, 2023 (1:15 pm)

Dear Dr. klinger,

A beautiful coastal oak located on my property (in Carmel-by-The-Sea) has been in slow decline over the past decade. As one of the tree’s trunks became infested with ants I unfortunately had to have the infested trunk removed. It’s been about two years since this was done and the tree’s health continues to decline. It’s an unusually beautiful oak and I’m ready to do almost anything to save it. I’m considering applying a full 5-lb. box of azomite to the tree’s perimeter. Should this be accompanied by an all- natural fertilizer such as Bio-Live 5-4-2?

I would be most appreciative of any recommendations you may offer in this matter.