CDR in the Tropics: Building Trust, Markets, and Climate Solutions

When Jill Raval steps onto a stage, whether under the lights of a classical Indian dance performance or in front of a global audience of climate entrepreneurs, she carries the same sense of rhythm and intent. “I wasn’t a good student,” she admitted with a laugh during the Pioneering CDR in the Tropics webinar hosted by Milkywire on October 8, 2025. “I was much more into dancing.”

Today, Raval serves as Milkywire’s Nature Lead, guiding the organization’s work at the intersection of science, philanthropy, and private-sector action. On this day, she moderated a conversation with two pioneering founders building tangible carbon removal systems in the world’s most dynamic and challenging regions: the tropics.

The speakers, Niklas Kluger, Co-Founder and COO of InPlanet, and Freddie Catlow, Co-Founder and CEO of Planboo, have each turned local soil and biomass into global-scale solutions. Together with Raval, they reflected on the process of creating an entirely new industry from the ground up.

Raval’s own story framed the session’s tone. Born and raised in India, she discovered her path to climate work almost by accident: through an elective course in environmental studies while studying in the U.S. “It shocked me,” she recalled, “to see the difference in how resources were used in the U.S. versus at home.” That realization propelled her into fieldwork collecting nitrogen and phosphorus samples, studying agricultural runoff, and later joining the UN Environment Programme.

Her path, from dance to data, and eventually to climate finance, echoes the challenge Milkywire now faces: turning distant climate pledges into action rooted in real landscapes and real people. On October 8, that ambition framed a simple but difficult question for the panel: how can carbon removal be built, trusted, and scaled in regions where the very foundations of a market are still being laid?

From Personal Missions to Planetary Work

Both founders’ stories began far from boardrooms or laboratories. For Niklas Kluger, the roots of InPlanet trace back to Brazil’s semi-arid northeast, where he worked with an NGO to restore the degraded Caatinga forest and support vulnerable family farmers. “That’s what really brought me back to Brazil,” he said. “Since then, I never returned to Germany.”

During that period, his co-founder, Felix, visited him. Surrounded by fragile ecosystems and dry soils, the two reflected on how to turn degradation into regeneration. “We wanted to create something impactful,” Kluger recalled, “something that could turn that around.” Their discussions culminated in an application to a climate accelerator, the moment that launched what would become InPlanet, a company dedicated to enhanced rock weathering (ERW) as a scalable carbon removal pathway for tropical agriculture.

Kluger’s scientific grounding was always tied to a social mission. His master’s thesis explored how carbon markets could fund reforestation and reverse desertification. By July 2022, InPlanet was legally incorporated in Brazil, and within just eighteen months the company achieved verified carbon removal credits from ERW, independently validated by external auditors.

Across the Indian Ocean, Freddie Catlow’s path to carbon removal began in a very different setting: a bamboo-framed construction site in rural Sri Lanka. “When I finished school, I had no idea what I wanted to do,” he said. “I worked in a nightclub to save up some cash, then moved to Australia and New Zealand to figure life out.” He then applied his studies in sustainable construction by helping build an eco-hotel in Sri Lanka’s national park, where he used bamboo for everything from structure to design.

The experience gave Catlow a new sense of clarity and confidence, a proof that sustainability could be both practical and rooted in community life. After returning to Stockholm, he reconnected with his future co-founder and joined a local climate-tech accelerator, where the idea that would become Planboo began to take shape.

Catlow described biochar as one of humanity’s oldest soil practices: organic residues burned in controlled kilns. He explained that the process isn’t new or overdesigned, but a revival of methods farmers have used for millennia, one which we now know can stabilize carbon for centuries.

From these two journeys, a new narrative of carbon removal has taken shape: CDR in the tropics as local craftsmanship, grounded in trust, tradition, and the power of place.

What It Means to Build in the Tropics

If carbon removal in the global North is a question of precision and policy, in the tropics it is a question of endurance and proximity. When moderator Jill Raval invited Kluger and Catlow to reflect on what it truly means to operate in the tropics, their first answers came with a laugh: “It’s really hot.”

That, however, was more than a joke. Kluger described days of fieldwork inside three-meter-high sugarcane, where the team collected soil and water samples under heavy heat and humidity. “Physically, it’s really tough,” he said. “I have so much respect for our team.”

But within that hardship lies what Kluger described as the tropical advantage: the same heat, rain, and biological intensity that make the region one of the fastest natural engines of carbon transformation on Earth. In such conditions, enhanced rock weathering happens more quickly, biomass grows faster, and nutrient cycles accelerate, turning the tropics into one of the most efficient landscapes for carbon removal.

Catlow agreed, adding that the tropics’ potential is not only physical but cultural. He described how his team spends much of their time traveling between regions, yet everywhere they go, they find echoes of practices that have existed for millennia. Biochar, he explained, is not an imported technology but a rediscovered one: long before carbon markets existed, farmers across the tropics were mixing charred residues with enzymes, urine, and crop waste to enrich their soils. For Catlow, this continuity between ancestral knowledge and modern climate practice is what gives tropical CDR its strength.

Yet it also demands a different mindset from both project developers and buyers. “We’re working in places where agriculture has been prescriptive for generations, big chemical inputs, top-down guidance,” Catlow said. “Now we’re asking farmers to do something that’s not on a billboard, that isn’t marketed by a fertilizer company, but that’s in their own power.”

Raval noted that changing long-standing agricultural practices takes time and tangible incentives. She emphasized that in the tropics, where most producers are smallholders, financial viability is often the deciding factor. Without alternative income or livelihood support, farmers are unlikely to take the risk of adopting unfamiliar methods.

Both founders acknowledged the tension. For InPlanet, Kluger explained, farmer adoption has been surprisingly high in Brazil, where more than 60 percent of producers already use biological inputs. “There’s a genuine interest in innovation and independence,” he said. “We see farmers experimenting, talking to neighbors, creating this kind of snowball effect.” Larger farms in central Brazil often dedicate hundreds of hectares to pilot projects, while smaller ones require more operational support.

For Planboo, the approach is necessarily collective. “We work through cooperatives and local organizations that already have trust,” Catlow said. “That’s how you get to scale, through networks that farmers already believe in.” By turning agricultural residues such as coffee husks, cotton stalks, bamboo waste, into biochar, these projects transform what was once burned or discarded into a visible, local form of climate action.

Despite the physical exhaustion and logistical hurdles, the founders insist the tropics offer something rare: speed, community, and purpose. They described the same heat and humidity that make fieldwork so demanding as also the driving force behind the region’s rapid biomass growth and intense carbon cycling, which are conditions that make tropical CDR uniquely powerful. In this way, the tropics become not just a testing ground for carbon removal technologies.

Trust as Infrastructure

For both founders, trust is the very infrastructure on which the tropical carbon removal industry must be built. Without it, no data, credit, or certification can carry meaning.

During the webinar’s final segment, Raval reflected on why Milkywire chose to support both InPlanet and Planboo through its Climate Transformation Fund. She highlighted InPlanet’s science-first rigor and Planboo’s decentralized, community-driven model as complementary approaches to credibility, adding that patience in building the science is itself a form of trust.

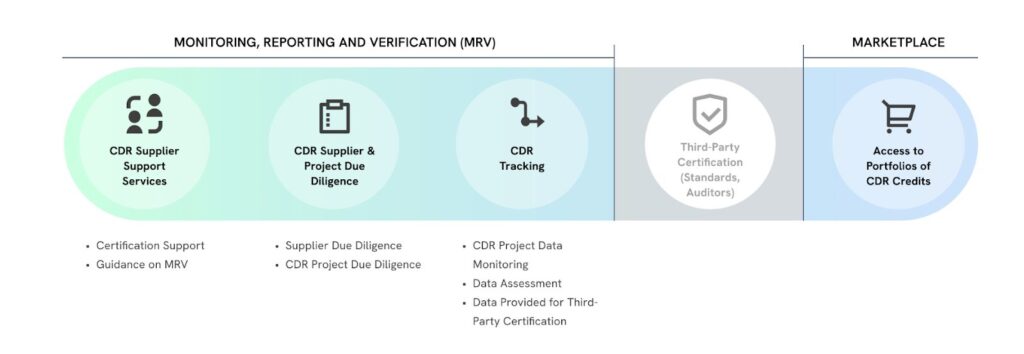

For InPlanet, credibility begins with measurement. Kluger described how his team spent months designing a monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) system that would hold up under scrutiny globally. Their soil-sampling design relies on subsampling, pooling, and paired analysis to balance representativeness with practicality. In regions where soil heterogeneity is low, they apply rarefaction methods to capture mineral and nutrient variability while keeping costs feasible.

Each experiment links field data to independent verification. Samples are analyzed under standardized laboratory protocols, cross-referenced with operational logs, and verified by third-party validation and verification body Eco Engineers under alignment with Isometric’s ERW methodology.

The outcome of that effort was groundbreaking, with verified enhanced rock weathering credits issued in late 2023. But Kluger sees that milestone less as a finish line and more as a proof of concept that transparency can create its own market gravity.

Technology as transparency

For Planboo, transparency is digital and distributed. Catlow’s team developed a dMRV (digital MRV) framework that pairs field-level data collection with real-time monitoring. Their proprietary Greenbox kilns capture temperature and gas emission data for every batch of biochar produced, reducing methane release by roughly 94 percent compared to traditional open-pit methods.

The data are transmitted and verified through project dashboards, allowing buyers, partners, and local cooperatives to track carbon removal and co-benefits in real time. That means accounting for every emission during transport, processing, and pyrolysis, subtracting them from the gross removal to yield a net sequestration value.

This creates a system that can grow across borders. It also ensures that farmers who are often smallholders with limited access to high-tech systems, can still participate in a market defined by data, not by scale.

Systems, Standards, and the Global South

Policy and standards are what give carbon removal in the tropics institutional shape. Both are evolving fast, and in some cases, faster than the projects themselves.

In Brazil, where InPlanet is based, 2024 marked a turning point. The country’s new Law 15.042/2024 established a national emissions trading system, the Sistema Brasileiro de Comércio de Emissões (SBCE), and introduced the Crédito de Redução Verificada de Emissões (CRVE), verified reduction credits that can be traded alongside voluntary offsets. The law’s explicit recognition of enhanced rock weathering (ERW) as a legitimate mitigation pathway has opened a door that few imagined even two years earlier.

For Kluger, this shift transforms ERW from an experimental science into a potential compliance mechanism. InPlanet’s first verified ERW credits demonstrated that rigorous measurement and local deployment could meet the world’s emerging quality benchmarks.

Across the Indian Ocean, Planboo is navigating a parallel but distinct policy landscape. In Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, the rise of voluntary carbon markets has created new space for biochar as a removal solution. Regional governments have been developing sustainability frameworks that encourage low-emission agriculture, while private certification bodies like Verra have advanced methodologies such as VM0044, that formalize how biochar projects can quantify and trade verified removals.

For smallholder farmers, these frameworks are gateways to participation. By connecting community-scale projects to global standards, Planboo’s decentralized system allows remote cooperatives to issue credits with the same integrity as large corporate suppliers.

Raval underscored the role of Milkywire as a bridge between these evolving systems. Through its Climate Transformation Fund and Catalytic CDR portfolio, Milkywire has supported both InPlanet and Planboo since their early days.

In many ways, patience defines the tropical CDR ecosystem. Across the tropics, local practice and international policy are turning early pilots into a recognizable carbon economy. Yet the aim is not merely to follow global standards but to reshape them, showing that credibility can emerge from the periphery as much as from established institutions.

Beyond Technology

By the end of the session, as questions poured into the chat, Raval paused to reflect on what connected these stories beyond their science. She emphasized that carbon removal is not only about extracting CO₂ but also about resilience and the people behind them.

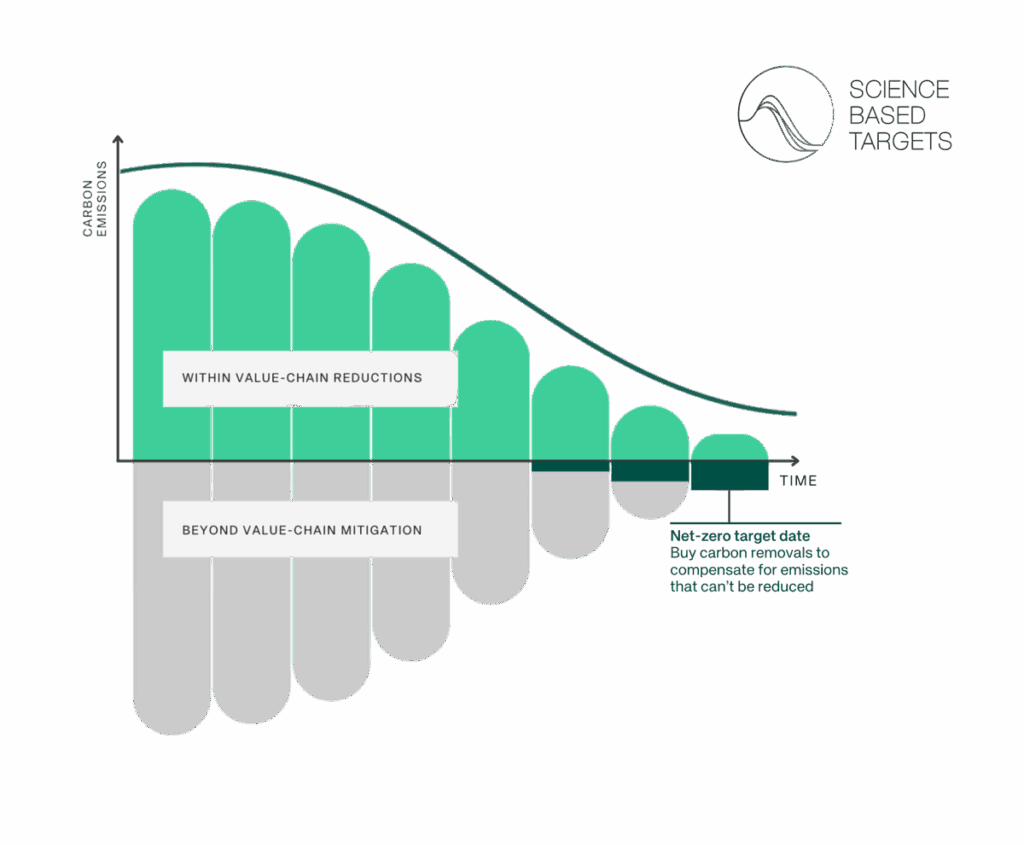

That statement captured the deeper logic of tropical carbon removal. In the global North, CDR is often framed through metrics: permanence, additionality, scalability. In the global South, it must also answer to justice: to who participates, who benefits, and who bears the risk. And this is where the tropical experience begins to look more like a blueprint.

Raval then closed the webinar with gratitude and a hint of awe. “This space is still evolving,” she said. “And maybe that’s the most exciting part, that we get to learn from it as it grows.”

From the basalt dust of Brazilian farms to the bamboo ash of Sri Lankan kilns, the new carbon economy is being written by people who see both climate and livelihood in the same horizon. In the tropics, climate action rises from the same soil that sustains life, showing that trust, like carbon itself, can be cultivated through care.

Qi Zheng is an undergraduate student in Environmental Policy and Sustainable Development with Economics at the London School of Economics and Political Science. She is interested in climate policy, soil carbon sequestration, and sustainable land management, and is also exploring the intersections of environmental governance and economic development.

Support us on Patreon

Thank you for joining us today! Please become a member of RTE and support us on Patreon. Unlike many larger organizations, we work with a team of determined and passionate volunteers to get our message out. We aim to continue to increase the awareness of remineralization to initiate projects across the globe that remineralize soils, grow nutrient dense food, regenerate our forests’ and stabilize the climate – with your help! If you can, please support us on a monthly basis from just $2, rest assured that you are making a big impact every single month in support of our mission. Thank you!

Got something to say?