Enhanced Weathering for Corn: Promise, Limits, Direction

Ilsa Kantola, during soil research at the University of Illinois (iSEE Research).

Two recent field studies, one published in PNAS (Beerling et al., 2024) and another in Global Change Biology (Kantola et al., 2023), offer the clearest evidence yet of how enhanced rock weathering behaves in the U.S. Corn Belt. Together, they quantify carbon removal alongside soil chemistry shifts and agronomic responses, and update the net carbon budget with real-world measurements rather than extrapolated estimates.

For a region where corn underpins feed, fuel, and processed foods, these results are embedded within practical decision-making. They also open the door to a sharper question that guides the discussion ahead: in the realities of modern corn systems, what kinds of change can enhanced weathering deliver?

Why Corn Matters

Corn sits at the center of U.S. agriculture in a way few crops do, as it shapes feed markets, anchors ethanol production, and supplies the raw material for a wide range of processed foods. Its influence extends beyond acreage and yield statistics, touching the logic of how calories are produced and priced. Michael Pollan once described this arrangement as an economy that keeps reinventing corn so it can be consumed in ever more forms. This is how industrial agriculture turns a single species into an expansive system of calories, additives, and feed inputs. That system relies on heavy fertilizer use to maintain consistently high outputs. As a result, soil function and environmental costs are tightly bound to production norms.

Any intervention that alters soil chemistry has consequences far beyond the field where the rock dust is applied. It affects crops that support livestock operations, processed food manufacturers, and regional economies, which is why the behavior of enhanced weathering in cornfields deserves closer attention.

Understanding corn’s structural role sets up a question: if enhanced weathering can shift the trajectory of this particular crop, what might that mean for the wider agricultural system built around it?

What These Studies Found

“Basalt application stimulated peak biomass and net primary production in both cropping systems and caused a small but significant stimulation of soil respiration.”

Kantola et al. (2023)

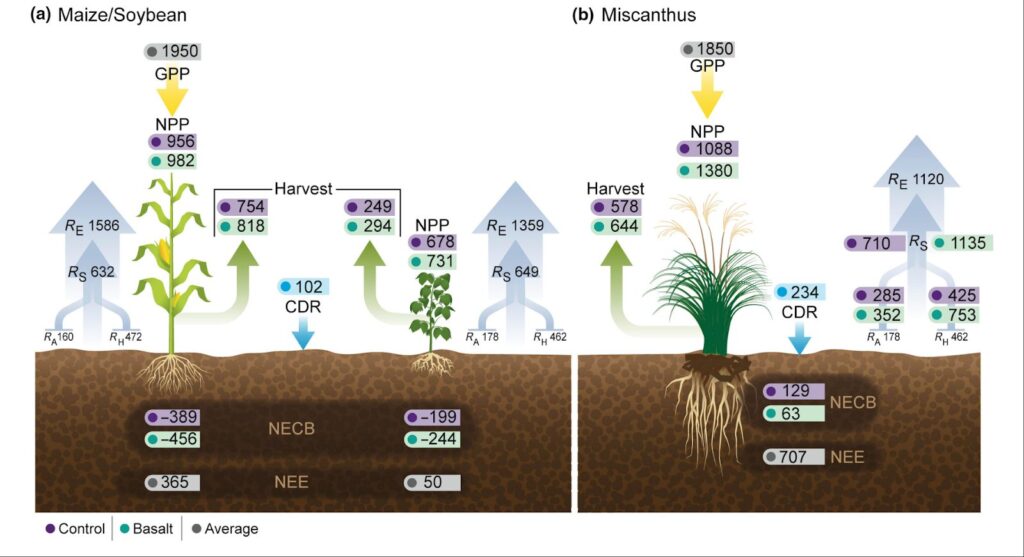

Kantola’s team approached enhanced weathering by asking where the carbon actually goes when basalt rock dust is applied to a cornfield. To answer this question, they traced the chemical fingerprints of weathering through the soil profile. As basalt dissolved, it released alkalinity that moved downward with water, carrying captured CO₂ in the form of dissolved inorganic carbon. Four years of field measurements indicate that this process removed roughly 102 grams of CO₂ per square meter per year, offsetting 23 to 42% of the crop system’s net carbon loss in the maize-soybean rotation. Tracking this movement allowed the researchers to update the net carbon budget with measurements taken directly from the field, giving a clearer sense of how much carbon remains stored over time.

They also observed steady shifts in soil conditions. The pH in treated plots rose, acidity weakened, and the release of calcium and magnesium created a more stable environment for root growth. These changes shaped the rate at which CO₂ was taken up and transported, grounding the carbon-removal numbers in physical processes rather than assumptions.

Beerling’s study looked at how enhanced weathering reactions play out in day-to-day farming. The added basalt rock dust served as a slow-acting soil amendment. It eased acidity, reduced the chance of aluminum stress in sensitive soils, and nudged nutrient balances into ranges that favor crop development. These results align with observations in related field sites, where basalt additions produced a consistent upward shift in pH, suggesting that these agronomic effects are reliable and stable.

A few sites saw yield gains, especially in fields that started with low pH or depleted cation levels. Others showed smaller improvements, such as more efficient use of applied nitrogen or better early-season growth. These outcomes are consistent with what growers often see when soil conditions improve enough for plants to respond.

Viewed together, the two studies give enhanced weathering a clearer profile. The chemistry that removes CO₂ from the atmosphere unfolds alongside changes that influence crop performance. This connection sets the stage for the next question: how can these effects translate into methods farmers can realistically use?

Why This Matters for Farmers

In many parts of the Corn Belt, growers have watched their soils change after years of fertilizer use and increasingly wet seasons. In these fields, any practice that slows that degradation in conditions reduces management pressure, without demanding a shift in crop strategy. What often stands out to farmers are the small, early signals, like roots moving more easily through the soil and steadier early-season growth, long before yield numbers change.

Adoption tends to follow practices that simplify management, and enhanced weathering seems to fit that description. It can be applied with familiar equipment and folded into existing fertility programs, while conditions adjust gradually rather than through abrupt shifts. For growers who are already juggling tight schedules and rising input costs, the appeal often lies in that predictability. It offers a way to improve soil function while keeping the overall system intact.

This is also where the connection to climate becomes practical. When a single amendment influences both soil conditions and carbon dynamics, growers gain more than a marginal adjustment, they gain an option that aligns agronomy with long-term resilience. That alignment is subtle, but it sets up enhanced weathering as a tool that fits into how many corn farms already operate.

Where Enhanced Weathering Reaches Its Limits

Corn production in the Corn Belt is held in place by external forces such as pricing structures and policy incentives. Those pressures shape fertilizer use and rotation patterns, and enhanced weathering works inside that framework instead of redefining it.

A major challenge is therefore the entrenched practices of industrial agriculture. Industrial corn production relies on heavy applications or nitrogen-based fertilizers, and a significant share of the region’s emissions arises from that application and nutrient losses and nitrogen runoff through drainage networks. Application of enhanced weathering can reduce dependence on nitrogen fertilizers and the need for pesticides, but if not paired with changes to industrial practices, it does not prevent all issues.

Industrial agriculture is also characterized by monoculture, where agricultural fields grow a single strain of a single crop season after season, bringing constraints such as tight rotations, pest cycles, and drainage infrastructure. These continue to shape field conditions independently of any amendment. Basalt can modify soil chemistry, yet the core ecological patterns of intensive corn will remain largely intact.

A final set of constraints emerges from logistics. Climate outcomes hinge on quarry distance, transport requirements, and the energy needed to produce fine rock powders. Farms far from suitable mineral sources may see reduced net removal as these costs accumulate. These frictions accompany any large-scale amendment program, although they become particularly visible across a region as vast and variable as the United States Midwest.

Focusing on these challenges demonstrates that enhanced weathering should be seen as one aspect of a broader strategy, such as regenerative agriculture. Enhanced weathering offers measurable gains in soil conditions and verified CO₂ removal, even as many structural features of the Corn Belt leave other problems to solve.

Areas for future research

“Most inorganic carbon formed by EW ultimately finds its way to deep ocean deposits where its turnover time is measured in millennia (Hartmann et al., 2013; Renforth & Henderson, 2017), making its storage essentially permanent, at least in the context of climate mitigation.”

Kantola et al. (2023)

Even with promising field results, several uncertainties shape how enhanced weathering might operate over longer timeframes. In practice, weathering rates measured over only a few seasons give an early signal, yet they cannot show how carbon persists as alkalinity moves through deeper soil layers over decades. There is also the question of ecological feedback. When silicate minerals accumulate in soils shaped by heavy fertilizer use, microbial shifts or nutrient imbalances may emerge in subtle ways that short trials cannot detect.

Economic feasibility adds another layer. Transport distance, energy use, and fluctuating carbon-credit prices influence farm-level decisions, and these factors vary widely across the Midwest. For this reason, longer studies and clearer policy frameworks will matter as much as the geochemical data.

Taken together, the studies show that enhanced weathering can remove CO₂ while improving soil conditions important for corn production. This combination gives the practice traction, especially where growers look for adjustments that support yield stability and require minimal disruption. Because basalt can be applied with familiar equipment and responds predictably in moderately acidic soils, it folds into existing management routines with relative ease.

Looking ahead, the value of enhanced weathering depends on two things working in parallel: more study of its long term benefits, and policies that provide clear accounting rules for carbon removal. If these elements align, the Corn Belt could incorporate basalt in a way that reinforces both productivity and climate goals.

In the long run, if enhanced weathering gains a foothold in corn systems, it may signal a moment when climate mitigation and everyday farming begin to move along a shared path.

Qi Zheng is an undergraduate student in Environmental Policy and Sustainable Development with Economics at the London School of Economics and Political Science. She is interested in climate policy, soil carbon sequestration, and sustainable land management, and is also exploring the intersections of environmental governance and economic development.

Support us on Patreon

Thank you for joining us today! Please become a member of RTE and support us on Patreon. Unlike many larger organizations, we work with a team of determined and passionate volunteers to get our message out. We aim to continue to increase the awareness of remineralization to initiate projects across the globe that remineralize soils, grow nutrient dense food, regenerate our forests’ and stabilize the climate – with your help! If you can, please support us on a monthly basis from just $2, rest assured that you are making a big impact every single month in support of our mission. Thank you!

Got something to say?