Rock Dust Crop Dusting: Pulverized Rock Makes for Effective Pesticide

As long as there has been agriculture, there have been insects, mites, and other creatures eager to share in the bounty. Pests remain an enduring problem for agriculture. Increasingly, communities are seeing even pesticides designed to deter or eliminate pesky insects become a liability as essential pollinator populations decline, unwanted toxins infiltrate crops—endangering farmers and consumers—and insects develop resistance to traditional deterrents and poisons. One possible solution: rocks.

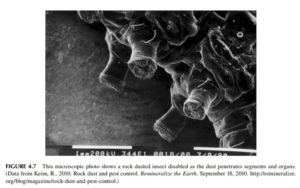

Crushed rocks, to be precise. Seeding mineral-poor soils with pulverized rocks not only introduces badly-needed nutrients to the plants they house, it also packs in a ready-made (and non-toxic) pest deterrent. Rocks, of course, have been kicking around far longer than agriculture; how is it they work as a pesticide?To be effective, the rock needs to be in a powdered form. This fine dust saps insects’ moisture by disrupting the waxy coating they depend on to keep from drying out. Moreover, rock dusts are abrasive: they get stuck under appendages and in joints—not terribly conducive to an insect’s usual sleek, coordinated movement of limbs and wings. Their gears get jammed, so to speak.

This “mechanical discomfort,” as it’s called in the field, is owed to one element of the dust in particular: silicates. The particles disrupt the insects’ tissues and movements. Adding to the effectiveness, once silicates are washed into the soil and taken up by the plant, they form a second defense: strengthened shoots that are naturally more resistant to predation by insects. Pest insects are opportunists and more readily ravage weak, unhealthy plants.

Mike E. Kelland, a researcher at the Leverhulme Centre for Climate Change Mitigation in the University of Sheffield in the UK, published a report with his colleagues this year detailing the effects of basalt rock dust applications in an agricultural context. They found that silicon is substantially taken up by plants treated with rock dust.

“Grasses like sorghum are silicon accumulators, naturally,” Kelland says. In his study, these agricultural plants increased their silicon concentration by 26 percent, in comparison to a control group.

“26 percent extra silicon is a big deal,” he says. “Silicon has beneficial effects for a range of different plants; not just for fungal pathogens, but also to resist pests. It can increase the strength of the stem, to prevent plants from being tipped over or blown over in the wind.” Healthier, stronger plants are naturally more resistant to pests than ill or weak plants for the same reason healthy people are better equipped to mount an immune response: they can better marshal their own natural defenses. That’s one bonus (among many) that traditional pesticides don’t include.Synthetic insecticides not only fail to strengthen plants, they unintentionally breed stronger predatory insects. Any approach that kills the target pest speeds the emergence of pests that are resistant to that pesticide or dose, necessitating a more potent poison or stronger dose and snowballing an arms race between pest and farmer. Flat-out decimating insects isn’t ideal either, as they’re a regular participant in any ecosystem, and play an essential role in their local ecologies. Conventional pesticides are poisonous to insects, and can’t discriminate between friend and foe. Neither can rock dust, but it’s also a deterrent, rather than a poison. Synthetic pesticides are listed as a major contributing factor to many insect species’ declines in a study published last year in Biological Conservation. Honeybees and other pollinators are collateral damage in the arms race.

In a more worldly—and to many, more pragmatic—vein, alternatives to traditional pesticides must be inexpensive. To rock dust’s credit, it is: just $8 (on the high end) can get you a ton of rock dust as a byproduct from a local quarry. Commercial versions designed for agriculture vary more widely, but a ton (enough for about one to two acres) can be purchased for around $200, according to Rock Dust Local.

It should be noted that rock dust is not a panacea to industrialized agriculture’s perpetual pest problem, but it is practical for sustainable farming. Since insects are deterred, rather than decimated, the area’s ecological milieu stays balanced.

A notable mark in rock dust’s favor is its non-toxicity to humans—those who farm and those who consume the produce alike. Some conventional pesticides are carcinogens, linked to various cancers, and others have been implicated in respiratory illnesses and even the neurodegenerative condition Parkinson’s disease. By contrast, rock dust may introduce a mild risk of respiratory complications accompanying extensive breathing-in of the dusts. This risk can be addressed, however, if those who use rock dust on a larger scale are advised to use a respirator during the application process—dependent on how it’s applied (wet or dry) and whether it’s a windy day.

A notable mark in rock dust’s favor is its non-toxicity to humans—those who farm and those who consume the produce alike. Some conventional pesticides are carcinogens, linked to various cancers, and others have been implicated in respiratory illnesses and even the neurodegenerative condition Parkinson’s disease. By contrast, rock dust may introduce a mild risk of respiratory complications accompanying extensive breathing-in of the dusts. This risk can be addressed, however, if those who use rock dust on a larger scale are advised to use a respirator during the application process—dependent on how it’s applied (wet or dry) and whether it’s a windy day.

Research on rock dust is ongoing, not only for its role as a pest deterrent, but also for other functions: putting nutrients into depleted soils, absorbing carbon dioxide, and improving soil ecology among them.

“We really do need to do much more research to find out how and why these effects are coming about,” Kelland says. “As the studies get bigger, and as interest grows in this kind of approach, we’ll need to do a lot more analysis of the source material. It’s very important. You want to know not only that you can capture carbon, but that it also delivers these other agronomic benefits.”

Natasha Strydhorst studied science journalism at Boston University and Writing and Environmental Studies at Calvin College. She is on the cusp of beginning a Ph.D. program in science communication. Her goal is to address, through her studies and work, science illiteracy—bringing a greater understanding of and curiosity for science into the public realm. Natasha enjoys reading, writing, the great outdoors, and virtually any combination thereof. She looks forward to expanding her own and others’ understanding of remineralization science.

Would you like to know more?

Support us on Patreon

Thank you for joining us today! Please become a member of RTE and support us on Patreon. Unlike many larger organizations, we work with a team of determined and passionate volunteers to get our message out. We aim to continue to increase the awareness of remineralization to initiate projects across the globe that remineralize soils, grow nutrient dense food, regenerate our forests’ and stabilize the climate – with your help! If you can, please support us on a monthly basis from just $2, rest assured that you are making a big impact every single month in support of our mission. Thank you!

Got something to say?